Viareggio – Castelnovo ne’ Monti

21 May 2025

185 km

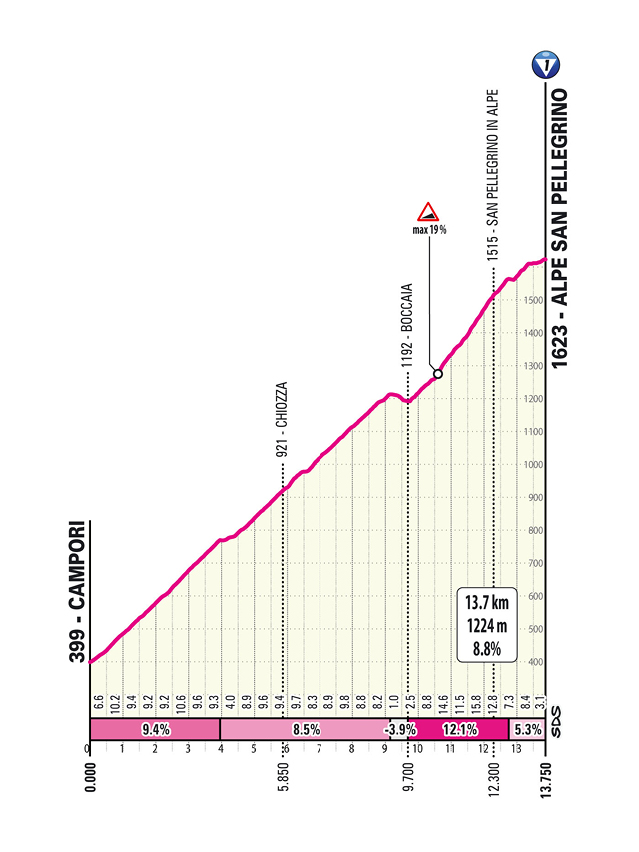

IMPORTART CLIMB OF THE DAY

GENERAL CLASSIFICATION (TOP20) BEFORE THE STAGE

1 DEL TORO Isaac (UAE Team Emirates - XRG)

2 AYUSO Juan (UAE Team Emirates - XRG) 0:25

3 TIBERI Antonio (Bahrain - Victorious) 1:01

4 YATES Simon (Team Visma | Lease a Bike) 1:03

5 ROGLIČ Primož (Red Bull - BORA - hansgrohe) 1:18

6 MCNULTY Brandon (UAE Team Emirates - XRG) 2:00

7 YATES Adam (UAE Team Emirates - XRG) 2:06

8 CICCONE Giulio (Lidl - Trek) 2:07

9 CARAPAZ Richard (EF Education - EasyPost) 2:10

10 ARENSMAN Thymen (INEOS Grenadiers) 2:27

11 BERNAL Egan (INEOS Grenadiers) 2:33

12 GEE Derek (Israel - Premier Tech) 2:37

13 CARUSO Damiano (Bahrain - Victorious) 2:38

14 STORER Michael (Tudor Pro Cycling Team) 3:14

15 HARPER Chris (Team Jayco AlUla) 3:18

16 PIDCOCK Thomas (Q36.5 Pro Cycling Team) 3:41

17 VACEK Mathias (Lidl - Trek) 3:43

18 PELLIZZARI Giulio (Red Bull - BORA - hansgrohe) 3:43

19 PIGANZOLI Davide (Team Polti VisitMalta) 3:53

20 RUBIO Einer (Movistar Team) 4:03

FACES FROM THE PELOTON/ITALIAN CYCLIST OF THE DAY

Luigi Malabrocca,

the cyclist who was fighting for the last palce of Giro d'Italia

IF YOU CANT STOP THINKING ABOUT THE ROMAN EMPIRE

Roman presence in the Apennines of Reggio Emilia

The Apennine mountains of Reggio Emilia, situated between the Po Valley and Tuscany, represent a region rich in history, yet often overlooked in broader narratives of Roman Italy. While not home to grand cities or monumental ruins, this mountainous landscape played a strategic and economic role in the Roman world, serving as a critical corridor for movement, rural development, and imperial control.

Pre-Roman context and Roman conquest

Prior to Roman expansion, the highlands of Reggio Emilia were inhabited by Ligurian tribes, notably the Friniates and Apuani. These indigenous groups practiced transhumant pastoralism and occupied fortified hilltop settlements. Their resistance to Roman control was significant, prompting military campaigns in the 2nd century BCE as Rome sought to secure its northern territories and consolidate the region known as Cisalpine Gaul.

By the late Republic, the area was formally annexed, and Roman influence began to manifest in infrastructure, agriculture, and administration.

Infrastructure: roads across the mountains

The most tangible legacy of Roman activity in the Apennines lies in its road network, which facilitated military movements, trade, and communication between Regium Lepidi (modern Reggio Emilia) and central Italy.

One of the most significant ancient routes was the Via Bibulca, believed to connect Reggio Emilia with Lucca via mountain passes near modern Castelnovo ne’ Monti, Toano, and Cerredolo. While not preserved in monumental form, archaeological traces and toponymic evidence suggest that segments of this route were adapted and reused well into the medieval period.

These roads were essential not only for logistics but also for integrating remote highland communities into the Roman administrative and economic system.

Rural settlements and material culture

Unlike urban centers such as Parma or Modena, the Apennines hosted predominantly rural Roman settlements. These included villae rusticae—agricultural estates engaged in livestock farming, forestry, and subsistence agriculture.

Strategic and symbolic landscape

The mountainous terrain also held strategic value. Elevated positions like the Pietra di Bismantova, a dramatic limestone outcrop near Castelnovo ne’ Monti, may have served as observation points or natural landmarks for ancient travelers. Though its specific use during Roman times remains speculative, its prominence in the landscape suggests it would not have gone unnoticed by Roman surveyors and travelers.

ITALIAN PAINTING OF THE DAY

Nestled today among the treasures of the Louvre Museum in Paris is a remarkable and dramatic painting: The Martyrdom of Saint Catherine by Lelio Orsi (1511–1587), a Mannerist painter whose roots lie deep in the Reggio Emilia region of northern Italy. Though lesser known than some of his Florentine or Roman contemporaries, Orsi’s work exemplifies the intellectual elegance and dynamic experimentation of 16th-century Italian Mannerism.

Lelio Orsi was born in Novellara, a small town in the Apennines of Reggio Emilia, and spent much of his career in the Emilia-Romagna region. He worked under the patronage of the Gonzaga family, the ruling lords of Novellara, and developed a style that reflected the complexity and refinement of the Mannerist movement. Influences from Correggio, Giulio Romano, and even Michelangelo are evident in his sophisticated use of perspective, elongated figures, and dramatic compositions.

This particular painting, dating from the 1560s, presents the violent and miraculous moment in the legend of Saint Catherine of Alexandria, a Christian martyr who was condemned to death on a spiked wheel — only to be saved by divine intervention when the wheel shattered. The wheel itself — shattered and powerless — sits as a broken symbol of imperial violence, while Catherine stands, serene and composed, amid chaos.

Orsi’s work is a superb example of Mannerist aesthetics: movement over balance, emotion over harmony, and symbolism over strict realism. In The Martyrdom of Saint Catherine, Orsi does not simply tell a story — he choreographs a spiritual drama, filled with grace and tension.

The influence of his provincial yet cultured upbringing in Reggio Emilia is clear. Far from the centers of Rome and Florence, Orsi developed a distinct voice — one that blended local religious devotion with avant-garde style.

TAKE A LOOK AT STAGES 11 OF THE OTHER GRAND TOURS

Take a look at Stage 11 of Tour de France 2025

Take a look at Stage 11 of La Vuelta 2025